In his tiny kitchen Lee is putting away the contents of two plastic bags. This is all he will eat for the next week, until he can make another visit to the food bank.

It’s mostly tins: oxtail soup, kidney beans, sweetcorn, ravioli, baked beans, tuna. There’s a couple of packets of biscuits and some out-of-date trifle sponge fingers; a box of chocolate-flavoured breakfast cereal, a litre of orange juice and a packet of pasta.

Fresh items are limited to whatever has been donated to the food bank that week so Lee unpacks of a packet of trimmed runner beans, three sunflower-seeded wholemeal rolls, and a red and a green chilli.

“Surely that won’t be enough,” I say, trying to imagine how these foodstuffs might be combined to make at least one meal a day for the next week. “Will you go hungry before next Monday?”

Lee nods.

“And what about the cereal? Have you got any milk to go with it?”

Lee opens his fridge, pulling out a half empty litre carton. “Sometimes you get long life milk but I’ve got this.”

“And what happens when that’s finished?” I ask.

He digs deep into one of his jeans pockets. “I’ve got £1.50 to buy some more,” he says. “And that’s it.”

Lee and I met for the first time just two hours ago. Monday is food parcel voucher morning at the UCAN and I was vaguely hoping I might find someone who I could accompany to pick up their supplies.

The UCAN staff all know Lee. They have supported him for some months now, most recently Rosanne has helped him apply for a citizen card – which the UCAN has paid for – so he’ll have the photo ID he needs for agency work. And for the past three weeks, they’ve given him vouchers for the food bank in town.

Up until November last year Lee had been working nights as an order picker at a fruit and veg warehouse. He enjoyed the work. One night he was ill, couldn’t get himself out of bed, and didn’t show up for work.

The next night he was still unwell and telephoned his boss. Apparently he’d already been replaced and his boss reported back to the Jobcentre that he had quit. In turn, the Jobcentre registered Lee as ‘voluntarily unemployed’ and has suspended his benefits for six months.

“It’s been getting me down, really down,” he says as Vanessa and I explain the idea behind the As Rare as Rubies blog, “I’ve been to the GP.”

“Come in tomorrow morning,” says Vanessa, knowing that today’s first concern is the food bank that opens just once a week. “We’ll make a list of priorities. It’s employment day and we can ask Cath to sit down with you. You’ve already spoken to Citizens Advice haven’t you?”

Pretty much every service the UCAN has to offer is relevant to Lee just now – employment advice, confidence-boosting, debt management, mental health support – and Vanessa is determined, as she now tells him, to get a team of professionals around him. But first, the food bank.

…. continued in The most generous

I’m not sure how much I want to disclose about Jason. He’s not sure how much he wants to tell. Being interviewed for this blog is a big deal in itself, a great step forward from six months ago.

This eighteen-year-old is on the Heartlift programme with Andrea and, by his own admission, he’s had plenty of challenges even before things came to a head last October. Up until then Jason had been living with his mum and four sisters. He has never known his dad.

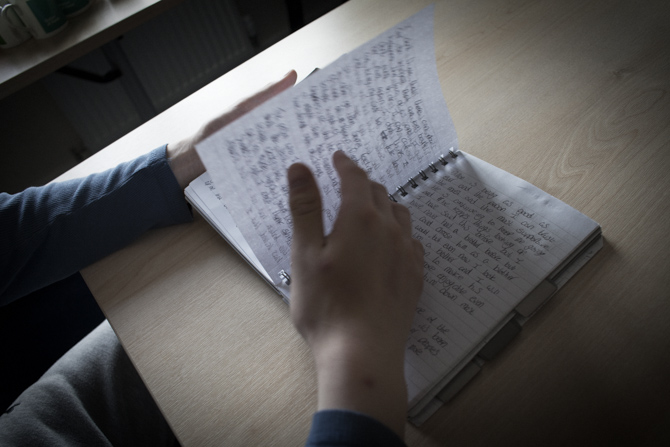

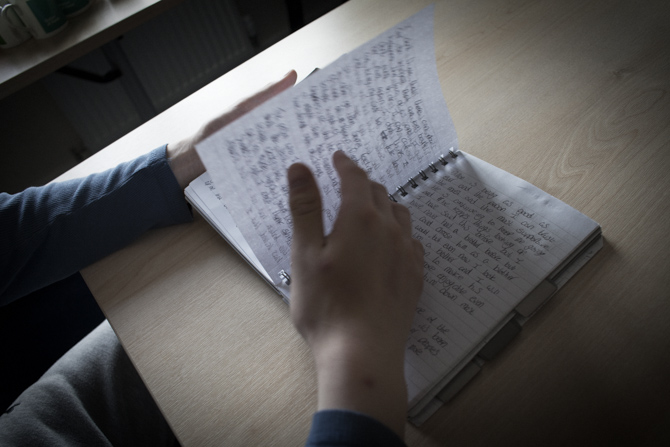

When I ask him to tell me something about the recent months he pushes his diary towards me. “Read the first few pages,” he says. And so I do.

Sunday 27th October

Now I am starting to realise what my problems are. Tackling them I think is to be able to talk about them. Hopefully I get out today so the tackling can start. I am going to start keeping a log book of day-to-day things and problems just to make things that little bit easier and I’m starting with this. There is still a lot of work to be done but now I feel I have paid the price for my ignorance. There is still guilt but I don’t think there is as much as what there was.

I’m already familiar with Jason’s diary. Andrea introduced us a few weeks back and asked if I would take a look, make some suggestions. I have already set Jason the challenge of typing out each entry so we can publish it on one of those print-on-demand websites and he can order copies.

“Tell me about your early teenage years,” I ask.

“I got kicked out of school at 13 because I was a little shit. I was swearing all the time, running round school, terrorising people. I got given a computer so I could work at home, but I didn’t do any work for two years.”

After doing nothing at home, Jason attended an engagement centre and scrapped some half decent passes at GCSE, including maths and English. He did less well at college.

“I didn’t go,” he admits. “I just gave up.”

Monday 28th October

Today started off a bit rough but it got better. Andrea has given me so much your support. I’m hoping that Andrea and the rest of the Heartlift team will be friends for life especially Andrea because I have never trusted anyone before. Andrea makes it easier to talk about things.

“How much has Heartlift helped you? Did they suggest writing things down?” I ask.

“It’s hard to put into words,” he says, “My life has just changed completely and yes, they suggested it. I’ve found it quite easy.”

“Do you finds it easier to write things down than to say things?”

Jason nods. “Uh-hu.”

I ask if I can photograph him with his diary. Maybe a silhouette of him against the window. He’s not sure so I take a couple and show him. We settle for him leafing through the pages.

My interview disintegrates into a discussion about writing. He has an idea for a novel he’d like to write. I recommend getting into the habit of writing something every day, anything at all. “Do you think you’ll always write? Have you found a new way to communicate?”

“Yeah,” he says, “I’ll always do it now.”

“Tell you what. I have an idea. Why not write something for this blog? A guest post. What about an open letter to David Cameron about what it’s like as a teenager on an estate like Breightmet.”

I walk through a bunch of teenage boys – and a cloud of marijuana smoke – to get to the front door this morning. Judging by the looks I get from those sitting at the nearest computers, some of the smoke follows me inside.

It’s only 9.30 and, as ever, the front room is already busy. Five of the eight computers are in use and I see job applications, emails and some online learning on the screens as I make my way to the back offices.

The UCAN isn’t open to the public every day but on these open access mornings Rosanne and Carl deal with a torrent of enquiries that sees them flitting from customer to customer, trying to keep all the plates spinning.

This morning I’ve decided to shadow Rosanne for as long as I can keep up, to get an idea of her role as a UCAN project officer.

By the time I have my notebook in hand she is already helping a young woman at one of the computers.

“How do I send this now?” asks the young woman. Rosanne points at the screen and reminds her how to send the email, an application for a job. “Brilliant. Thank you.”

Another woman is standing in the middle of the room, waiting her turn. “Do you know what I do with this?” she asks, holding out some papers.

Rosanne scans the form and passes it back, “Next, you need to list everyone who is moving with you. Then please let me see it again before you send it. Do you need an envelope?”

Back in the small office from which Rosanne keeps on eye on comings and goings there is a small huddle of colleagues. Vanessa is leading a discussion about the homeless alcoholic man who is frequently outside their parade of shops. Minutes later the huddle breaks and Rosanne is out into the front room again.

“Hiya, are you all right?” she says to a man who has just side stepped the ‘cannabis crew’.

“Can I use the phone please?” he asks. “Do you have the number for Jobseeker’s?”

As Rosanne’s pointing out the numbers pinned up above the customer phone, another man is signing in, the front door barely having had time to close. This customer wants to use a computer.

“You might be better off with this one,” she says, directing him to one of the computers which is less temperamental. These machines get a lot of use and some are more reliable than others.

It’s not always clear to me which customers are new to the UCAN as Rosanne treats everyone as if she has known them for years. But within minutes – and after she has exchanged pouches with a colleague delivering the internal mail – she is telling this new arrival about the Tuesday job club which suggests he’s not a regular. “And then there’s the Clear Aims course which is brilliant,” she says. “Cath here can tell you more about that, if you’re interested.”

Next Rosanne is answering the telephone. “Half past 12,” she says to the caller. “Then work club from 1.30 til 4.00. Okay, see you then.”

She comes off the phone, beaming. “Why so happy?” I ask.

“That woman on the phone was referred by the Jobcentre. She was told to ask for Rosanne because ‘she’s fantastic’!”

A young mum has just appeared at the office door, gently pushing her daughter in front of her. “She’s starting nursery this afternoon, at the big school,” she declares. “Show Rosanne your uniform, Kelly.”

Kelly proudly peels back her coat to reveal a brand new blue sweatshirt. Rosanne makes a fuss over the little girl and she and her mother leave happy, only to be replaced by a middle-aged woman who looks as if she hasn’t slept in days.

“I’m being made redundant, Rosanne,” says the newcomer, barely able to contain her tears.

“Come and sit down,” says Rosanne, offering the only other chair in the room.

“Can I make you both a brew?” I ask as the office door is closed behind them. I’ve managed about 15 minutes.

…continued from Fit for work?

At the hospital we eventually find the right place and are promptly ushered into a standard consulting room where a pleasant nurse – she tells us later she used to work on a drug and alcohol team – explains the procedure and starts asking questions.

She works through each of Richard’s symptoms: ADHD, alcohol dependency, hearing loss, anxiety and depression, and asthma and asks the same questions for each, typing his responses. “What are the symptoms of your ADHD?”

Richard is nervous. “Lack of concentration, confusion,” I recall he says.

She asks who diagnosed the condition, when, what tests did they do? When was the last time he saw a medical professional about this condition? She asks about his medication and then a series of standard questions about his daily routine. Can he cook for himself? Can he use a microwave? Can he wash himself? How often does he use the toilet at night?

The questions are rigid and formulaic. When she asks if he can use a microwave to heat and cook food Richard replies he can’t cook but he does heat food. “I can’t differentiate,” she says, “I’ll put down, cook and heat.”

The inadequacies of these ATOS assessments are well documented elsewhere but the irony of Richard’s situation isn’t lost on me. His ‘headline’ symptoms are an inability to concentrate and a tendency to get confused and here he is, sitting on the edge of his chair, being expected to articulate expansive answers to these quick fire questions and build his own case for staying on a disability benefit.

Throughout the half hour assessment the nurse makes it clear that she is not the one who will make the final decision. That will be left to a Department of Work and Pensions case manager who will read the report having never met Richard.

“I was expecting to be able to go into more detail about my own personal circumstances,” he says on our way back. “There should have been more on the emotional side, how ADHD affects me.”

“Although I barely know you Richard, I think I found out more about you in our thirty-minute journey there than she did in that formal interview.”

“You’re right. You did. I was much more relaxed.”

“Do you think you can work?” I ask.

“My concentration levels only allow me to do things in small quantities. It would need to be something I enjoy, something I can focus on. Anything boring or mundane, then I just wouldn’t be able to stick with it.”

“And as it stands now, you’re an alcoholic. Do you think you could actually hold a job down? Could you leave the house at eight and come back at six without having a drink?”

“No. No, I couldn’t.”

His appointment is at 9am at the Royal Blackburn Hospital, two buses and a train away or half and hour in the car.

Richard can’t manage public transport on his own. He gets panicky. He’d asked his social worker and his alcohol team worker. Both were unavailable to take him which is where I stepped in. He gets a much-needed lift, I get another story for this blog.

So now, having met in a Morrison’s car park, we’re driving through the East Lancashire countryside in the rain, discussing his ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder).

“How does it affect you on a daily basis?” I ask.

“My concentration levels are really, really low,” he says. “I’m always thinking of 100 things at once and I can’t stop it. It’s very frustrating. I can’t organise myself.”

“So what are you thinking about now, as we’re talking?”

“I’m thinking about this wonderful scenery, about the detox and about the questions they are likely to ask me this morning.”

Because of his ADHD, his alcohol dependency and his depression and anxiety, Richard currently receives Employment Support Allowance, a benefit which means he’s unfit for work. However, he does volunteer at the UCAN on a Monday afternoon, helping IT freelancer, Charlotte get people online.

As part of the welfare reforms, he has a controversial ATOS interview this morning to assess whether he should be put on a different benefit.

In 300 yards turn left.

“I’ll give you another example,” he says. “I can completely zone out. I might start crossing a road and not realise it. It’s a miracle I haven’t been knocked over by now.”

Richard is 34 and he tells me he’s been drinking and using drugs since he was 14. “The last 10 years have been full-on addiction but I’ve only admitted it these past five years.”

He’s waiting to be admitted on a three-week hospital detox, although it’s not the first time he’s tried to stop.

“I’ve come off in the past, just to prove a point, but that’s not the same, is it? This one is for me. Because I want to change.”

As well as the detox, his psychiatrist has changed his ADHD medication and booked him on Cognitive Behavioural Therapy sessions – talking therapy – for the next couple of years.

“You’ve got quite a journey ahead of you, haven’t you?”

After 300 yards turn right and then bear right.

“I’m scared though. Because alcohol is all I know. It’s going to be hard.”

Richard’s two-hour volunteering session at the UCAN is a lifeline at the moment, the highlight of his week. “I went to do an IT course there and was shocked when Charlotte asked me to volunteer. I can manage it for a couple of hours and, because it’s something I’m passionate about, I can focus on it for that short time. Now I’m buzzing.”

In 300 yards, you have reached your destination.

Continued in “Do you think you can work?”